It is a

commonplace that since the 1970s, capitalism has left the western working class

as roadkill on the road to globalization. What is new about our contemporary

moment is that the same is increasingly true for the Euro-American middle

class.

Be kind,

forward wind. What if, despite all the recent left’s hesitation about prophecy,

we still feel something is going to happen? Perhaps we are in a similar moment

to the early 1960s – only four or five years away from a ‘May 1968’ moment,

with all its spontaneous eruptions and consequential structural rearrangements.

Do we need

a weatherwoman to recognize the winds of insistence for change blowing through

the Middle East, the Mediterranean basin, the ‘north’ Euro-American cities, and

Latin America, let alone the vastly under-reported tensions elsewhere? If all

these are social trembles, foreshadowing a greater quake, how ought we to prepare

in the streets, the classrooms and all the interconnecting spaces in between?

Some

preliminary answers come through the keywords: neoliberalism, occupy, and

world-system. Within the last decade, ‘neoliberalism’ has replaced

‘globalization’ as the preferred term to describe the latest regime of

capitalist accumulation.

Thanks to

writers like David Harvey and Naomi Klein, we have a common sense about

inequality-producing tactics that overlap and reinforce each other. These

maneuvers include privatization, deregulation, financialization, return to the

watchman state of police surveillance, opportunistic austerity, and crony

collaboration among financiers, civil society institutional administrators, and

political elites.

Neoliberalization

Yet we

still need to consider the difference between neoliberalism and

neoliberalization: not just a matter of academic term splitting. The terms

differentiate between an unchanging, homogeneous thing-form—an ‘ism’— and a

process that involves multiple, sometimes contradictory, processes—an

‘ization’. While social actions do cross thresholds to achieve a nameable

consistency, like neoliberalism, we also need to remember the fluxes of an

“ization” for, at least, two political reasons.

Firstly,

the use of the latter term prevents us from losing our nerve and slipping into

demobilized apathy. While market fundamentalists certainly do have the upper

hand at the moment, they are by no means a juggernaut. Resistance is not

futile, Dorothy!

‘Neoliberalization’

reminds us that social movements of right and left are constructions of tactics

and coalitions. What was built up over decades by the right can also be

disassembled and replaced. The reconstruction of a broadly articulated left

will need a host of generalizing and particularizing analyses and actions.

Secondly,

the term neoliberalization also reminds us that the current moment belongs to a

longer history of capitalist class struggle. Because capitalism is

fundamentally an organization of the circuit of value through commodity chains

of labor-power, raw materials, and energy inputs, neoliberalism has to be

placed in context with prior moments.

Capital volume I’s emphasis on telling a history of

sequential ages of capitalist developments (the Age of Handicrafts,

Manufacture, Large-scale Industry, etc.) looks to define historical

periodization, the differences between one time and another. But Marx also

sought to consider capitalist periodicity, repeating or recurring capitalist

activities. Perhaps neoliberalism seems new only because it presents the return

of capitalist logistics that have not been dominant for some time, or even

within an older generation’s active memory.

Neoliberalism

might be the reappearance of capitalist tactics that have been dormant, but

never forgotten or absent. Consequently, we need to return to the entire set of

Marx’s

Capital and Gramsci’s

Prison Notebooks to relearn the

manifolds of capitalism and the construction of Left coalitions. David Harvey

has encouraged us to relearn the later volumes of

Capital; we still need voices for Gramsci. The so-called posthumous

writings of Louis Althusser, those written after his incarceration, especially

the essay ‘

Marx in his Limits’ or the

shortly to be published Verso translation of

On the Reproduction of Capitalism are good starts.

Gerard Duménil and Dominique

Lévy’s

The Crisis of Neoliberalism

uses long-wave economic theory to provide a longer perspective and argue that

post-1800 capitalism produces two kinds of recurring crises. They call these

inflections a crisis of profitability and a crisis of financial hegemony. Both

types result in shifting alignments as what they call the

professional-managerial class either cleaves to the business class of haute

capitalists or the ‘popular’ (working) class. Crises of profitability have

appeared in the 1890s and the 1970s. When the professional-managerial class

becomes frightened that their prerogatives are being eroded by rising

proletarian empowerment, they grant the business class the right to take profit

in return for managing to subordinate workers.

Duménil and Lévy see neoliberalism as an

interlocking set of tactics arising during the 1970s within a returned crisis

of profitability. They understand privatization, deregulation, and financialization

less as goals in themselves (no matter what capitalist ideologues might

proclaim), than as a means to an end. Capitalists’ target here was the rising

standard of living for labourers and the waves of racial, sex-gender, and

postcolonial democratization signposted by the phrase ‘May 1968.’ As a result,

government was to be transformed into a watchman state mainly dedicated to

securing monopolies of private property and the abandonment of public oversight

into corporate criminality.

The other kind of crisis that Duménil and Lévy

discuss is the one of financial hegemony, seen during the 1930s. In this phase,

the middle classes lose faith in capitalists’ ability to manage society. The

middle classes, often reluctantly, begin to divorce themselves from their

thrall to high capitalists and seek to promote their own members, like John

Maynard Keynes, as having superior technocratic skill in social arrangements.

In order to wrest themselves from control from

above, the professional-managerial classes seek working-class

support by regulating speculators and redirecting speculators’ capital

investment towards social welfare and entitlement schemes in return for a more

stable period of decreased labour unrest. We variously call this realignment

the New Deal (USA), the Welfare State (UK), or the social market (continental

Europe).

The current

moment, especially after 2008, is likewise a crisis of financial hegemony, a

period that allows otherwise technical terms, like neoliberalism, to become

common even outside the academy.

Derivatives

A crisis of

financial hegemony also means that previously held truths become questioned.

One example involves our explanation regarding credit derivatives. The

traditional definition of derivatives is that they are trades based on the

exchange of an underlying commodity. For example, the future price of pork

bellies becomes itself a number to be speculated upon. What was originally a

means of hedging against market unpredictability then become a means to

commoditize risk, a means to sell price variability as if it were the commodity

rather than any actual usable object.

There is a

received history of the rise of derivatives involving the convergence of new

mathematical equations to calculate risk (canonically, the Black-Scholes

equation); the technological revolution allowing for the massification of

computer power that can handle these equations, beginning with the handheld

calculator in the 1970s; deregulation of banking that allowed speculators

access to vast new pools of capital that had otherwise been effectively

illiquid due to post-Depression era restrictions, such as the Glass-Steagall

Act of 1932; and the rise of a new generation of bankers who were culturally

more comfortable with risk than the post-war cohorts.

Yet what

this story still mystifies is that in all likelihood derivatives are probably

no more or less profitable than other kinds of speculation. Derivatives become

seemingly profitable only through the unexamined presence of corporate

criminality that manipulates systemic determinants, as seen with the LIBOR

scandal; the use of offshoring treasure islands, as Nicholas Shaxson calls

them, for tax avoidance purposes; and the generation of lucrative transaction

fees for bankers at the expense of all other parties, who are often reluctant

to whistle-blow, since it would have career damaging prospects for the

corporate executives or government officials who personally negotiated these

agreements.

In this

sense, we do not have to outlaw derivatives, since they effectively only work

through already illegal procedures. If the above lines seem convincing to you

reader, it is because the presence of a crisis of financial hegemony has

already prepared you to consider claims that would have seemed almost

inconceivable had they been written ten years ago.

Occupy Wall Street – a realignment waiting to happen

If Duménil and Lévy are

right that we are amidst neoliberalism’s crisis of hegemony, then Occupy Wall

Street’s fusion of college graduates and labour unions was a realignment of

interests waiting to happen, due to larger structural forces.

Occupy Wall Street came, if anything, too

late. The tenth anniversary of 9/11 had to happen undisturbed, otherwise police

repression in the vicinity of the Twin Towers would have been swift and sealed

by mainstream media consent. Yet the late September start meant the summer

months were lost and from the start they faced the challenges of colder

Manhattan.

Occupy Wall Street’s breakthrough was to

catapult a language about inequality, austerity, and neoliberalism beyond the

containers of the academy or small press left journalism. In an age of the

Murdoch contamination of media, this alone was an achievement and prepared for

the next wave.

In this light, Occupy is best considered as a

dandelion movement: a failure in its own limited terms of composition, but a

success as its dispersed seeds float to root more broadly elsewhere.

The crisis

of 2008 made visible the cracks in the hegemonic culture of neoliberalism

wherein the middle-class was encouraged to assume a lifestyle of the rich,

famous, and wealthy through debt burdens that individuals had been previously

warned against. Yet several left economists, like Michel Roberts in

The Great Recession, suggest that 2008

was only a forewarning of a much greater downfall that may occur in 2014. David

Wiedemer, Robert Wiedemer, and Cindy Spitzer’s

Aftershock makes similar arguments, but they are less willing to

settle on a precise date.

Counterpunch’s

Mike Whitney repeatedly delivers forensic arguments on the fragility of the

post-2008 bandage of fiat fictitious capital for bankers and austerity for the

rest of us.

Middle class realignment come what may

Even if a

cataclysmic moment does not happen over the next few years, the process of

middle-class realignment will continue for reasons suggested by Immanuel

Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi as they argue that we are coming to the end of

a long-wave configuration in the capitalist world-system.

It is a

commonplace that since the 1970s, capitalism has left the western working class

as roadkill on the road to globalization. What is new about our contemporary

moment is that the same is increasingly true for the Euro-American middle

class. For this group is not simply facing a momentary downturn of stalled

wealth accumulation, but a more general developmental crisis as the core of the

capitalist-world-system moves eastward to South and East Asia.

In this new

phase, business interests have themselves sought a new class trophy partner,

abandoning the western bourgeoisie for a more vibrant East and South Asian

nascent middle class. Global capital, consequently, has stopped caring about

the Euro-American bourgeoisie’s present longevity and sees it as little more

than a meat puppet ready for asset stripping by increasing the cost for those

non-negotiable elements taken as defining middle-class identity: home

ownership, higher education, healthcare, and pension security.

As the

certainty of any generational transfer of accrued wealth becomes less tenable,

the middle class becomes more willing to realign and work with the working

class, not because it has become more socially egalitarian, but because it has

become more frightened.

One

cultural expression of this fear of falling is the recent mass popularity of Gothic

tales that hyperbolically display the splatter of a middle-class character’s

stuffing. Neo-Gothic fiction, films, and television conveys less a forlorn

inability to imagine democratic alternatives to apocalyptic release, than an

initial inconvenient self-truth. Many of the most popular, such as AMC’s

The Walking Dead, stage realignments

where the working-class characters, like the “white trash” Daryl rise in

authority and fan popularity, not due to their muscularity or sharp-shooting,

but by the more middle-class characters’ and viewers willingness to listen to

working-class figures and work alongside (or underneath) them.

Similarly,

the popularity of green-thinking and esoteric practices, like yoga, can be read

as a bourgeois means of adjusting to a lack of purchasing power that the

working class always had, through a self-protecting rhetoric that makes it seem

as if downward consumption was the bourgeoisie’s free choice, rather than a response

to structural pressure.

A similar

gesture may exist within all our discussions of neoliberalism. For every

critique of capitalism’s erosion of civil society, no matter how abstruse or

elitist sounding, also prepares the way for what Raymond Williams called a new

structure of feeling.

Truly

progressive change can come about even when some of its most active collective

agents do not necessarily seek the full implications of their own movement. For

this reason, the Left more than ever needs to think once more about the ways in

which we organize within the ongoing transformations.

Whether we call such planning the communist

‘hypothesis’ or ‘horizon’, as

Jodi Dean has

suggested, the main point is that history has no place for regret for those who

tarry.

This article is part of an editorial partnership between

openDemocracy and the Centre for Modern Studies at the University of

York. It was funded by the University of York's Pump Priming Fund, the

British Academy, and York's Centre for Modern Studies.

It is a

commonplace that since the 1970s, capitalism has left the western working class

as roadkill on the road to globalization. What is new about our contemporary

moment is that the same is increasingly true for the Euro-American middle

class.

It is a

commonplace that since the 1970s, capitalism has left the western working class

as roadkill on the road to globalization. What is new about our contemporary

moment is that the same is increasingly true for the Euro-American middle

class.

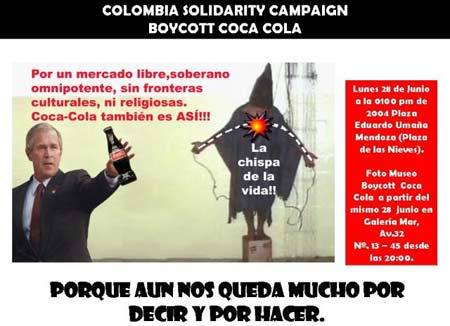

Foto: “Específica para el dolor de cabeza. Alivia el canscancio físico y mental”

Foto: “Específica para el dolor de cabeza. Alivia el canscancio físico y mental”

Fotos: “apoya la salud cardiaca de la mujer”

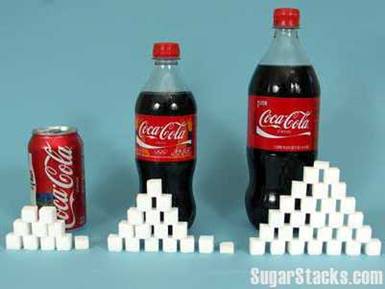

Fotos: “apoya la salud cardiaca de la mujer”  Foto: ¡Impensable, imbebible!

Foto: ¡Impensable, imbebible!

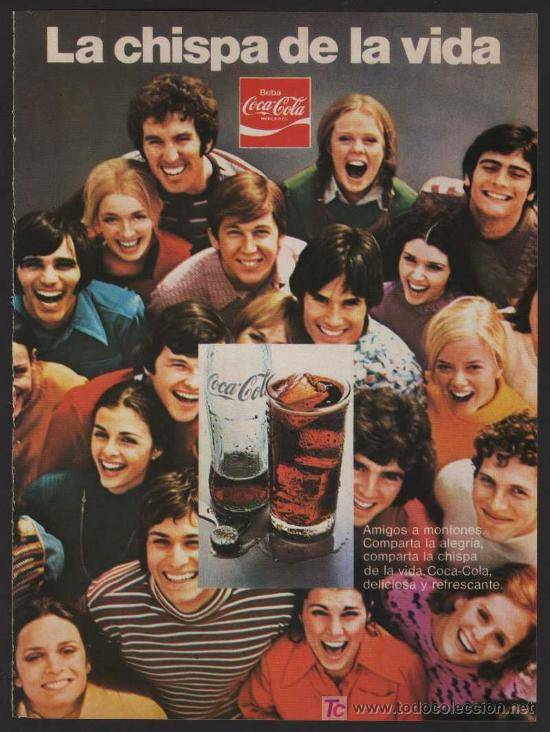

Foto: Ejemplos del aumento de la hipocresía publicitaria de la compañía.

Foto: Ejemplos del aumento de la hipocresía publicitaria de la compañía.

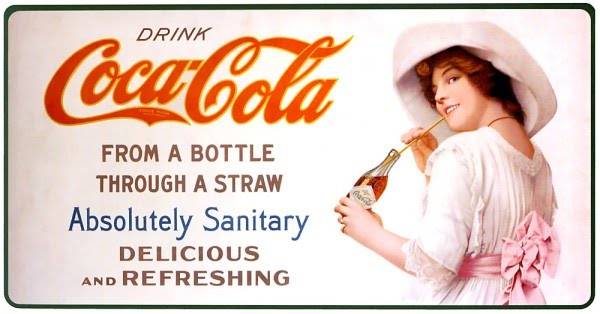

Foto: Ejemplo de publicidad “sana”.

Foto: Ejemplo de publicidad “sana”.  Foto: Ejemplos de publicidad “servida en los mejores hospitales”.

Foto: Ejemplos de publicidad “servida en los mejores hospitales”.

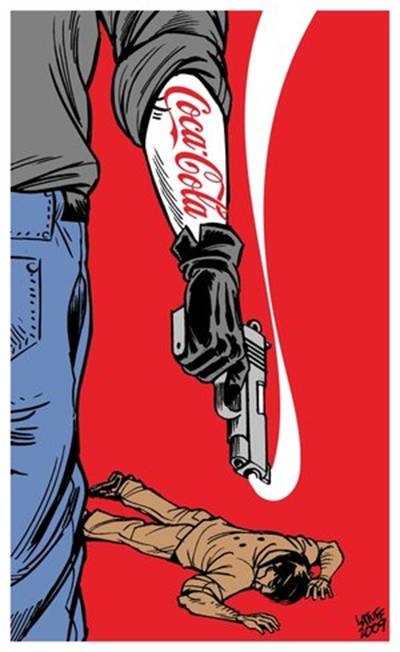

Foto: ¡Impensable Imbebible!

Foto: ¡Impensable Imbebible!